WWRD U.S. v. United States is exactly the kind of case that makes me love what I do. Much like our recent foray into sunflowers seeds, this case seems to have a simple answer that gets derailed by the law. It has to do with some potentially festive articles, which is also one of my favorite legal topics.

The question here is the classification of several examples of tableware that are decorated with Christmas or Thanksgiving motifs. The items have names like "Old Britain Castles - Pink Christmas" and "12 Days of Christmas crystal flutes." Customs and Border Protection classified the merchandise in various headings based on their composition. The plaintiff protested and asserted that the merchandise is specifically designed and intended for use in conjunction with Christmas or Thanksgiving dinners. According to plaintiff, that makes the correct classification HTSUS item 9817.95.01, which reads:

The history of this provision is interesting. After a lot of litigation, in 2007 the HTSUS was amended to clarify when utilitarian articles are "festive articles" related to holiday celebrations. The amendment added Note 1(v) to Chapter 95, which excludes from Chapter 95 "Tableware, kitchenware, toilet articles, carpets and other textile floor coverings, apparel, bed linen, table linen, toilet linen, kitchen linen and similar articles having a utilitarian function (classified according to their constituent material)."

This change caused a related problem. Changes to the HTSUS are supposed to be revenue neutral. Removing these items from the duty-free provisions of Chapter 95 resulted in an increased rate of duty. To fix that, the ITC added 9817.95.01, which is also duty free and avoids the messy issues of classification as festive articles.

What all that means is that because of Note 1(v), these products cannot be classified in Chapter 95. If they are not classifiable in 9817.95.10, then CBP correctly classified them according to their constituent materials. So, what about 9817.95.10?

A lot of the legal analysis is about breaking down text to find its correct meaning. Doing that to 9817.95.01, we find that merchandise classifiable there must be:

The question here is the classification of several examples of tableware that are decorated with Christmas or Thanksgiving motifs. The items have names like "Old Britain Castles - Pink Christmas" and "12 Days of Christmas crystal flutes." Customs and Border Protection classified the merchandise in various headings based on their composition. The plaintiff protested and asserted that the merchandise is specifically designed and intended for use in conjunction with Christmas or Thanksgiving dinners. According to plaintiff, that makes the correct classification HTSUS item 9817.95.01, which reads:

Articles classifiable in subheadings 3924.10, 3926.90, 6307.90, 6911.10, 6912.00, 7013.22, 7013.28, 7013.41, 7013.49, 9405.20, 9405.40 or 9405.50, the foregoing meeting the descriptions set forth below:

Utilitarian articles of a kind used in the home in the performance of specific religious or cultural ritual celebrations for religious or cultural holidays, or religious festive occasions, such as Seder plates, blessing cups, menorahs or kinaras . . . .

The history of this provision is interesting. After a lot of litigation, in 2007 the HTSUS was amended to clarify when utilitarian articles are "festive articles" related to holiday celebrations. The amendment added Note 1(v) to Chapter 95, which excludes from Chapter 95 "Tableware, kitchenware, toilet articles, carpets and other textile floor coverings, apparel, bed linen, table linen, toilet linen, kitchen linen and similar articles having a utilitarian function (classified according to their constituent material)."

This change caused a related problem. Changes to the HTSUS are supposed to be revenue neutral. Removing these items from the duty-free provisions of Chapter 95 resulted in an increased rate of duty. To fix that, the ITC added 9817.95.01, which is also duty free and avoids the messy issues of classification as festive articles.

What all that means is that because of Note 1(v), these products cannot be classified in Chapter 95. If they are not classifiable in 9817.95.10, then CBP correctly classified them according to their constituent materials. So, what about 9817.95.10?

A lot of the legal analysis is about breaking down text to find its correct meaning. Doing that to 9817.95.01, we find that merchandise classifiable there must be:

- Classifiable in 3924.10, 3926.90, 6307.90, 6911.10, 6912.00, 7013.22, 7013.28, 7013.41, 7013.49, 9405.20, 9405.40 or 9405.50

- Utilitarian

- Of a kind used in the home

- In the performance of specific religious or cultural ritual celebrations for religious or cultural holidays, or religious festive occasions

There was no controversy surrounding the first three elements. The sole question before the Court was, therefore, whether these items are used in the performance of specific religious or cultural ritual celebrations for religious or cultural holidays, or religious festive occasions.

Ask yourself whether Thanksgiving dinner is a specific cultural ritual celebration? It is a specific cultural celebration. That seems to be clear. After all, we all know what that looks like, right?

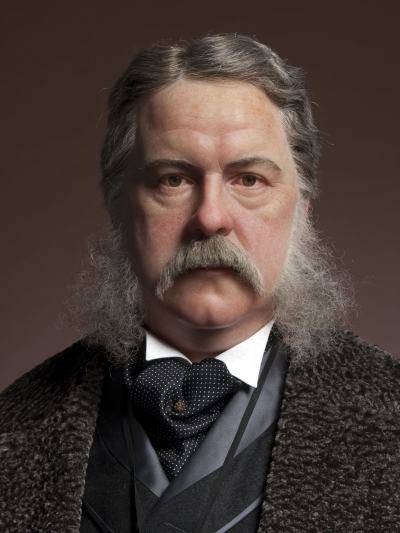

| Normal Rockwell's Freedom from Want via a Quinta Arts Foundation |

But, is the imported tableware part of a "ritual celebration?"

We all have family rituals for Thanksgiving dinner. Do you have to hide the alcohol before Uncle Abe arrives and starts mixing overly sweet Old Fashioneds? Does Grandpa insist on carving the turkey his special circa 1975 electric carving knife? Does little Jenny come back from Berkeley to lecture everyone on the evils of industrial turkey farming while being the sole person willing to eat her tempeh loaf and non-gmo cranberries? How about when the entire assembled family simultaneously leans back from the table just enough to loosen their belts and newly-tight pants and then moves in for pie?

I am less comfortable opining on Christmas rituals. I can, however, say with certainty that my personal Hanukkah ritual involves using a curved carrot peeler as an implement to clear candle stubs from the menorah each of the eight nights. Another widespread ritual is the discussion among knowledgeable Jews of exactly the best means of accomplishing that task. Add to that the ritual second degree burns inflicted on the poor bubbe tasked with frying the latkes or, in fancy households, the sufiganyot. The latter should look familiar to Rustbelt residents who enjoyed paczki this week.

The legal problem is that while those may be rituals in a colloquial sense, they are not rituals in a tariff sense. According to the Court of International Trade, a ritual is "a customarily repeated often formal act or series of acts." That means it is something done the same way, using the same steps, every time. A ritual is essentially scripted and can be reduced to the instructions necessary to accomplish it. That is distinct from the raucous and chaotic family gathering around the Thanksgiving or Christmas table.

That understanding of "ritual" is consistent with exemplars in the tariff item. Seder plates, for example, are part of the ritual Passover Seder. "Seder" means "order" and the important ritual of every Seder is telling the story of the redemption from salvery in Egypt. The event is so ritualized that there is a manual given each participant.

No matter what crazy things happen at any particular Seder, there is a defined ritual for telling the Passover story. It involves four cups of wine, four questions, and a plate full of symbolic foods. Often, the evening ends with a debate over whether Charlton Heston was better in The 10 Commandments or in The Omega Man, but that is not in the haggadah.

Plaintiffs in this case lost because the Court of International Trade found that a family dinner is not a "ritual," even when it falls on Thanksgiving or Christmas. In other words, every celebration is not a ritual celebration. With no ritual involved, the dinnerware could not be classified in 9817.

Note to the tableware industry, you might want to take a lesson from Maxwell House Coffee and start printing instruction books for Thanksgiving and Christmas dinner.